"Gesture and Program": On self-obsolescence

We return in "Gesture and Program", among other things, to Leroi-Gourhan's account of the self-limiting development of evolution. On the one hand, the material analysis circumscribes the possibilities of individual freedom within the constraints of a given techno-gestural epoch; the operational sequences it has on offer. On the other hand, the transitions between epochs are given as a series of liberations of the body from its biological milieu and, in the previous chapter, toward newfound lucidity. The body struggles to free itself from its constraints and, in the process, determines new ones. Even if these liberations are at the same time credited to an irrevocable tendency toward externalization in gesture itself rather than to the actions of free individuals, exactly. At a minimum, the accent is on the former and not the latter. Individual choices made in freedom appear paradoxically as the fuel of broader natural historic necessity.

It is unclear, after all, what it would mean for a human, increasingly accessorized to machines and the programs that run them, to choose self-obsolescence. (A paradox that, at a similar time and same place, Sartre was wrestling with in his Critique of Dialectical Reason, to again stoke the flame of comparison.)

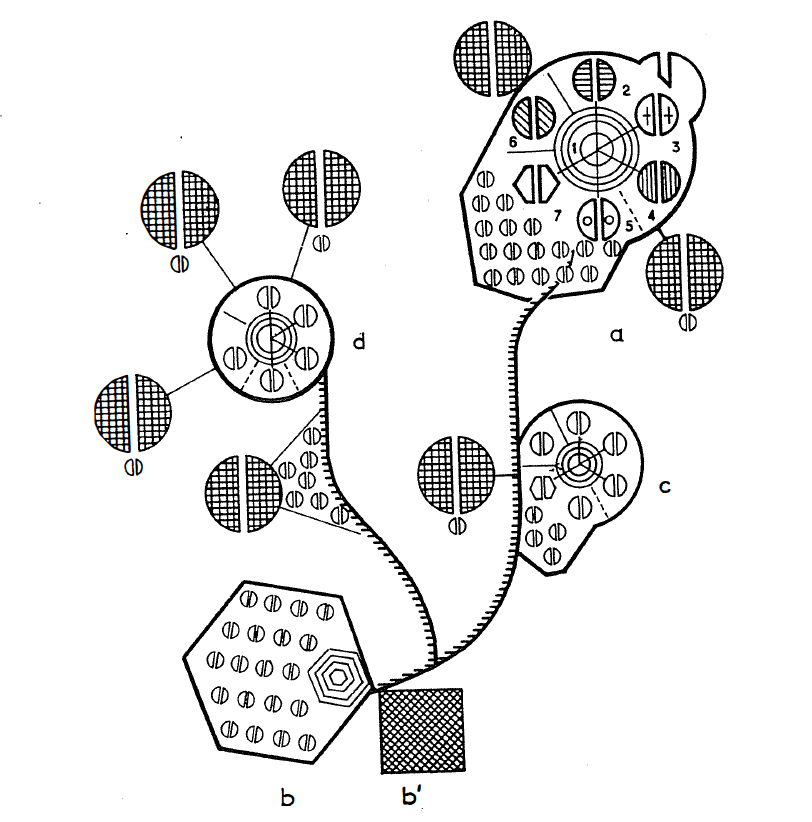

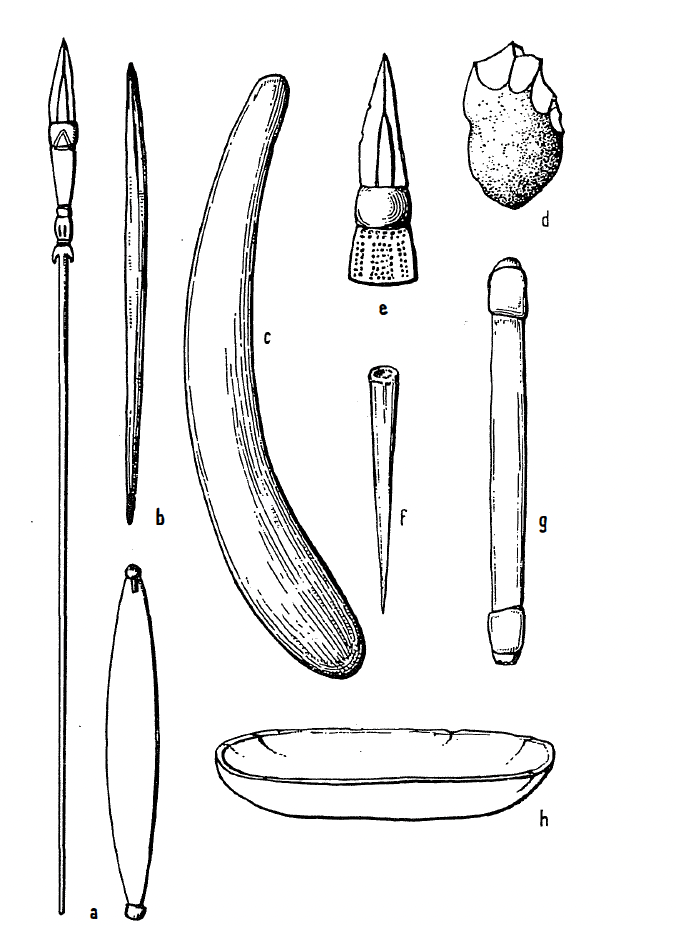

The question of self-obsolescence is raised first with reference to the hand and then extended to the body. The hand, to be sure, is in steep decline after its “apparently interminable heyday” “from the Upper Paleolithic to the nineteenth century”. To L-G, the course is set for the continuing migration of technical faculties out of the anatomical body itself, such that the species may soon experience the body as above all an encumbrance! A sort of provocative natural historical framing to Agamben’s claim that, in modernity, we are losing our gestures. (In order, L-G would say, to find them again at a higher level—that of the composite technological body.)